Tag: review

Sam Reviews: Hannibal

by ravenbait on Jul.17, 2013, under Reviews, television

![]() Something has to be exceptional to end up reviewed on this blog. There are a number of ways to be exceptional, but most of the time I review something either because it’s very, very good or because it’s really, really bad.

Something has to be exceptional to end up reviewed on this blog. There are a number of ways to be exceptional, but most of the time I review something either because it’s very, very good or because it’s really, really bad.

Hannibal, the TV series currently showing on Sky Living in the UK, depicts Thomas Harris’s eponymous serial killer during the time prior to Red Dragon, when Jack Crawford was hunting the Chesapeake Ripper.

And it’s very, very good.

I’ve seen mixed reviews of the series, and I’d not expected to like it. Hannibal Lecter, for me, is one of the great character inventions of modern fiction. He’s a serial killer who isn’t the typical sociopath or psychopath. He’s a man of refined tastes. He eats the rude, and that, for me, is delicious. I disliked what was made of the character in Hannibal Rising — Harris took something monstrously pure and gave it a reason to be. He tried to make Lecter a sympathetic character, someone for whom we should feel pity and understanding.

I think Lecter would have despised him for that. Lecter needed no reason to be. He just was.

Bryan Fuller, who developed the series, has stated that he consciously tried to imagine what David Lynch would do with a Hannibal character. But that doesn’t mean this is Twin Peaks with a more expensive taste in wine and patisserie; this is dark, eerie, intelligent, moody and stylish.

Lecter is portrayed by Mads Mikkelsen (who narrowly pipped David Tennant for the role) with admirable restraint and good-natured, predatory grace. Although initially doubtful, having previously seen him as the unnamed warrior in Valhalla Rising, I was won over within a couple of episodes. His accent is going to make it difficult for him to speak perfect Tuscan when he finally gets his job in Florence, but it’s perfect for this series. He has a poise and presence that make him eminently believable as the psychiatrist whose solution to dodgy flute playing is fine dining.

Will Graham, the FBI profiler with the empathy disorder, is played with beautiful sensitivity by Hugh Dancy — who, it must be said, would make a fine Doctor on the back of this performance. His performance was one of the factors that hooked me in the first episode. Over the course of the series — we’re up to episode 11, with a further 2 to go in this season — his portrayal of deterioration has been believable and moving.

The other cast members also do a good job. Will’s doctor friend, Alan Bloom, for this series has become Alanna Bloom, played with forthright conviction by Caroline Dhavernas. Freddie Lounds, the Tattler reporter who loses his lips to the Tooth Fairy in Red Dragon, is also played by a woman in this version, which should make the reinvention of that scene, when it comes, very interesting indeed.

Best of all is the writing. There is a very strong team here, including (huzzah) a woman writer — Jennifer Shuur. (She might be the only one so far, but that’s one more than Doctor Who, at least.) There is nothing in the storytelling that is wasted. There are no plot elements there purely for the sake of being there. This isn’t one of those series where there’s a different story every week with some meta-arc crowbarred into the plot, punctuated with a Hulk smash double episode just to make sure. Every single element of every episode is related, in some way, to the overall arc. Everything — everything — is about Will and Hannibal, which makes it all the more remarkable that it’s not immediately obvious exactly how the relationship is playing out, and yet, once it’s clear, the clues have been there all along. In everything. This is what I call fractal storytelling, and it gives me goosebumps. Exposition, the technique of stating everything explicitly, just to make sure the audience understands, is a strange attractor. Everything weaves and twines around it without ever touching it. I’ve not seen a television series do this comprehensively in a very long time; nor one to place such trust in the intelligence of the audience.

It’s not perfect. I’d be worried if it were. In the last couple of episodes the depiction of real medical conditions has been slightly haphazard and the writers have cherry-picked symptoms to fit the story (a particular bugbear of mine). This is, however, my only complaint to date, and the number of people who will be familiar enough with obscure conditions like Cotard’s and Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis to pick up on where artistic licence has come into play is probably small.

Bryan Fuller has done a fantastic job and I can’t wait to see what he’s going to do with the rest of the material.

Sam Reviews: Hide Me Among The Graves

by ravenbait on May.24, 2013, under books, Reviews

Hide Me Among the Graves by Tim Powers

Hide Me Among the Graves by Tim Powers

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

With Powers’s books I’m used to reading stories that make me feel the author knows his protagonists far better than anyone else who has ever written about them. They are mythic, mythical and full of iconography and symbolism. I read Declare and felt that the Cold War had been completely misinterpreted by historians the world over. I knew it hadn’t been, but that wasn’t the point. I felt that it had. I’m used to coming to the end of his books with a view of the world set slightly askew from the one I had when I started.

Sadly, Hide Me Among the Graves didn’t do that for me. Perhaps because there were both too many and not enough similarities to the London of The Anubis Gates, or perhaps because Christina Rosetti (familiar to more in these days of Doctor Who from the lines of “Goblin Fruit” quoted in the episode Midnight) as a character didn’t come through as the passionate, emotional, fey woman who wrote:

Yet come to me in dreams, that I may live

My very life again though cold in death:

Come back to me in dreams, that I may give

Pulse for pulse, breath for breath:

Speak low, lean low,

As long ago, my love, how long ago!

There’s always a danger, when using historical figures, that their depiction the work of fiction is not quite true to the reader’s idea of that person. It’s possible to wave away any differences by pointing out that this is a fictional work, and the universe of the story is not our universe. However, for me Powers’s magic as a storyteller has always been to make me believe, for the period in which I am reading, that it is our universe; and for ever after wonder if there are elements of his universe in this one and I just haven’t noticed.

I didn’t come away from this one feeling our universe might be slightly more magical than for which I’d previously given it credit. There was something missing, some spark that should have melded everything into a cohesive whole. For me it was rather like one of those dishes on Masterchef in which each component is beautifully cooked but the dish doesn’t quite work.

This is an accomplished work, but I’m used to being astonished by Powers, my perspective forever slightly changed. This was a very good story, well-written and entertaining. There is nothing wrong with that. It’s simply testament to Powers’s skill as a writer that previous exposure to his work left me disappointed with this one.

Sam reviews: Minister of Chance Episode 4 – The Tiger

by ravenbait on Mar.22, 2013, under Reviews

![]() As a MoC supporter, I’ve had my talons on a copy of episode 4 for a while now (by which I mean a couple of weeks) but other projects have kept me from listening.

As a MoC supporter, I’ve had my talons on a copy of episode 4 for a while now (by which I mean a couple of weeks) but other projects have kept me from listening.

Sorry, Dan. Hope this makes up for it.

It has been a while since we last visited Tanto, and those of you who have already been swept up by the series might want to go back and listen again to previous episodes. Those of you who haven’t — this isn’t the best place to start. They’re all free, so there’s no excuse for not downloading all of them and catching up. I’ve tried to keep this review spoiler-free, but comments on the story will make more sense if you have some idea of the context. You can also check out my reviews of previous episodes using the MoC tag.

Episode 3 left us in the middle of diverging story arcs and with a number of questions. Episode 4 set about weaving those story arcs back together and answering some of those questions.

It started with a scene of high action, in which a major character (spoilers!) hijacked a vehicle that shall forever in my head be called War Rocket Ajax. We were then given a nice portrayal of Professor Cantha in her new role as Science Advocate for the Resistance — no Ben Goldacre, the Professor; Jenny Agutter did a good job of showing the hesitancy and discomfort of a science hermit pressurised into the role of rationalist preacher. There were shades of Monty Python — when Cantha spoke of a man finding an apple tree, a heckler called, “And he made cider!”

She’s not the Messiah…

We finally discovered the Horseman’s goal, and a little more about him. Maybe a little more is enough, given that the role he performs is somewhere between Judge Dredd and the Predator, measured into a blender with a dose of Time Lord and pulsed until smooth. From his conversations with Kitty, stilted as they were, we are left with the question of whether every Time Lord considers himself and his fellows to be walking weapons of mass destruction, and, again, what was it that brought them here — not to Tanto, specifically, but this particular set of worlds.

There was also the big reveal, of course, although I’ve been bound not to give away any major plot details, so you’ll have to listen to find out that one for yourself.

The immersive quality of the production hasn’t diminished, although I found the mix levels a bit off in places in this particular episode. It was especially noticeable during the first scene with the Minister and the Horseman — the sound effects and music combined to make speech a little hard to hear and you might find it useful to fiddle with the sound settings on whatever device you’re using to give priority to vocals. I also wonder if a brief guide page would be useful, and perhaps one of the Minister Moguls with more time on his or her hands than I have might oblige with a page listing the major characters and locations. Jura and Durian, for instance, look very different on paper, but don’t sound that different. Personal preference, perhaps, but a crib page would help with things like that and also assist with the inevitable fade from memory that happens in the gaps between episodes — not a problem if you listen to them back to back, of course.

The characterisation, as always, is superb. There were some great one-liners and exchanges, particularly where Kitty is involved:

“Give us some food.”

“It don’t grow on trees, you know.”

“Yes it does!”

Then there was the Witch Prime’s (Sylvester McCoy) comment to Durian (Paul McGann):

“Charm only carries you forward. It won’t let you stand still.”

Given Professor Cantha’s apparent faith in the idea of linear cause and effect, the notion that the soon-to-be Witch Prime Emeritus was referring to the quark rather than the personal attribute amused me.

Dan Freeman should be proud of what he’s accomplished with this series. The writing balances satisfying complexity with an awareness of the limitations of the medium. He’s not afraid to expect the listener to pay attention and use his or her grey matter, and it’s a relief to be trusted to work it out for myself. At the same time, he has given us enough information, whether in dialogue or soundscape, to be able to work it out for ourselves, thus avoiding frustration. Hindsight is, after all 20:20. He also devotes effort to character interaction, something of which we don’t get to see (or hear) enough these days. MoC is an oasis in a desert of writing aimed at short attention spans requiring high drama and plot-driven storytelling. Freeman shows it is possible to have excitement and pace without foregoing sophistication.

Episode 5 is in production at the moment and I have high expectations. I’m sure I won’t be disappointed.

Sam reviews: Vibram Fivefingers Lontra

by ravenbait on Jan.08, 2013, under gear

![]() Anyone who has spent enough time in my presence to notice my shoes will know that I’m a committed user of Vibram Fivefingers (VFFs), and have been for the last three years. I am rarely found in anything else when travelling on foot. Initially I started wearing them because they allowed me to walk properly and run again after a serious foot injury. Now I wear them because normal shoes feel weird and wrong, not to mention resurrecting the problems that made me turn to barefoot living in the first place. I have KSOs for work and Bikilas for running.

Anyone who has spent enough time in my presence to notice my shoes will know that I’m a committed user of Vibram Fivefingers (VFFs), and have been for the last three years. I am rarely found in anything else when travelling on foot. Initially I started wearing them because they allowed me to walk properly and run again after a serious foot injury. Now I wear them because normal shoes feel weird and wrong, not to mention resurrecting the problems that made me turn to barefoot living in the first place. I have KSOs for work and Bikilas for running.

The problem is, of course, that I live in a maritime climate at a similar latitude to Gothenburg, Yekaterinburg and Fort McMurray. That means that most of the year it is wet, and in the winter it is wet and cold. Outdoor pursuits that involve walking or running in VFFs are out for a large chunk of the year. My damaged foot does not tolerate being cold and wet and VFFs are neither warm nor waterproof.

Or rather, they weren’t.

December 2012 saw the long-awaited release of Vibram’s new insulated and/or waterproof models, the Lontra (and its LS variant) and the Speed XC. To say that I’d been champing at the bit to get hold of a pair is something of an understatement. I’d heard about their coming release back in September and my race season generally starts in March. Losing an entire winter’s training could have scuppered my comeback so I went as far as emailing the UK distributors of Vibram, as well as Vibram Europe and Vibram US.

I think I must have been one of the first UK residents to order a pair, direct from Italy just before Christmas. As I’ve got on so well with the Bikila and the KSO I went for the Lontra as the strap fastening and the neoprene cuff appealed. The shoes arrived on Hogmanay, and our trip down to Fife to see my parents was delayed as I refused to go without them.

They had their first outing on New Year’s Day, on a walk that took us across muddy farmland, along the beach, and back up a muddy path.

First off, this should not be your first pair of VFFs. If you do not already own a pair, this review is of no use to you. Go and try a pair of Classics or KSOs or Treks first. Then you can come back. The reason I say this is because the laminated, water-resistant fabric is very stiff and the fit is snug. I spent 15 minutes getting these on the first time and if my toes didn’t already know what to do I think I might have failed.

If you already own a pair and the fit is on the tolerable side of small, get a size up from your usual. These are tight. The thicker material and overall stiffer shoe affects how your foot sits inside. I have quite small toes — my big toe is indeed my biggest, my little toe is tiny — and the fit is bearably small rather than comfortable. My other VFFs have a tiny gap at the end of the toes and using socks is not a problem. If you live in a very cold climate and want to wear socks then you may find the recommended size too snug for comfort.

You’ll notice from that image that there is a neoprene cuff and an extra loop at the front. If you try putting these on the way you put on KSOs you’ll be there for a while. The instructions are no different, but I would suggest pulling the neoprene up over the heel far enough that the rear loop is accessible and the heel is up against the main body of the shoe, then working the toes into place with the aid of the front loop, and only then pulling the heel up and settling into the heel cup. These are not shoes to use in an offroad triathlon if you want a fast T2.

This may also not be the model for you if you have moderate to high arches. I don’t consider myself to have a particularly high instep, but as you can see from the picture the fastening strap only just reaches the fluff for the velcro. It pops off repeatedly, to the point of irritation. I don’t understand why the shoe has been designed like this, as all it would take is another inch or two of strap and it wouldn’t be a problem. It’s not as if they are worried about putting velcro on the strap — there is plenty of it, but the strap itself is too short. Out of curiosity, I decided to see how compressed the shoe got if I attached the strap near the start of the velcro. Below you can see the shoe done up this way and done up without any compression.

Done up to give a proper foot shape, any flex pops the strap. If I do it up tightly enough for the strap to remain attached, I get painful compression over the top of the foot and my right big toe goes numb. All for the want of an inch or so of strap. It’s mind-boggling.

Performance-wise, these more than live up to expectations. They are warm and cosy, and, although billed as water-resistant rather than water-proof, kept my feet dry through mud, shallow rockpools and even a brief foray into the sea to retrieve a ball a toddler had lost. They let in a spot of wet when I used a jet of water from a hose to wash off the mud, and I can’t complain about that.

Some feedback is lost as the footbed is well constructed to protect against rocks and give traction on slippy surfaces. I had no problems walking over pebbles and rocks, and felt sure-footed over mud. The fleecy liner is comfortable against bare skin — I have not worn them often enough to judge what the infamous funk is like.

All in all these shoes do what I hoped they would do in terms of letting me get out and about in the cold and wet. I am mystified by the strap design, and wish I’d known about the tight fit before I bought them. I would probably have gone for the next size up. I would also have given serious consideration to getting the LS variant, which offers more room for high arches, although I suspect I would still have chosen this model because it has the neoprene cuff. In an ideal world Vibram would offer an LS model with elastic laces and a neoprene cuff, or add a couple of inches to the strap on the Lontra.

For summer walking in the wet these will most likely be too warm and the Speed XC might be the better option.

If you feel the same way about ‘normal’ shoes as I do, then Vibram’s new water-resistant range perform brilliantly in terms of keeping out the wet and the cold. Assuming they are all like the Lontras, they are sized ever-so slightly on the small side; and the Lontras have a serious issue when it comes to the strap design. They aren’t cheap, but there’s not much to choose from when it comes to waterproof, insulated, barefoot shoes.

They are definitely a shoe for the enthusiast, and I hope Vibram will improve on the design to make them a more comfortable, forgiving winter option.

Sam reviews: WOTW 2012

by ravenbait on Jan.04, 2013, under music, Reviews

![]() No one would have believed, in the last years of the 19th century, that human affairs were being watched from the timeless worlds of space. No one could have dreamed that we were being scrutinized as someone with a microscope studies creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. Few men even considered the possibility of life on other planets. And yet, across the gulf of space, minds immeasurably superior to ours regarded this Earth with envious eyes, and slowly, and surely, they drew their plans against us.

No one would have believed, in the last years of the 19th century, that human affairs were being watched from the timeless worlds of space. No one could have dreamed that we were being scrutinized as someone with a microscope studies creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. Few men even considered the possibility of life on other planets. And yet, across the gulf of space, minds immeasurably superior to ours regarded this Earth with envious eyes, and slowly, and surely, they drew their plans against us.

Thus speaks Richard Burton’s inimitable, mellifluous voice at the start of the 1978 Musical War of the Worlds, Jeff Wayne’s most famous creation. My mother has eclectic musical traits (a trait I am endlessly grateful to have either inherited or had inculcated) and a copy of this has been in her music collection for as long as I can remember. It may be a dreadful thing to confess, but this was my introduction to H G Wells and was one of my formative speculative fiction experiences. As a girl of primary school age, my initial reaction was one of awe: never would I consider bacteria the in the same way as I had. My mum has been known to tell family friends that my first comment was, “I’ll never put bleach down the toilet again.”

That’s what good speculative fiction should do. Change the way you think.

The sound effects, chilling in isolation and fed through the score until the guitars became gibbering Martian voices while the synthesisers spat blistering heat rays and spread shivering fronds of red weed across the soundscape, remain as effective now as they ever were. The actors and musicians, used to working live in front of theatre audiences and minus the visual extravaganzas now employed, conveyed their roles with conviction and feeling. The depiction of the Thunderchild crew sacrificing themselves and their ship to save the passenger liner is something I can clearly visualise to this day, despite never having physically seen more than an artist’s impression in the album’s accompanying booklet.

I can see an Ironclad warship going down under the irresistible assault of a Martian heatray, because Jeff Wayne’s composition utterly nails it.

Many years later I picked up an album called Ulludubulla Volume 2, which I reviewed at the time. There I said I didn’t see any reason not to update a musical, but overall the album didn’t really work for me. It was not, however, a remake of the original, but a series of tracks inspired by it.

2012 saw a brand new version of this iconic album hit musical theatres and CD/MP3. Richard Burton’s part is now played by Liam Neeson and David Essex’s artilleryman has been given to Ricky Wilson of the Kaiser Chiefs. Justin Hayward’s part is sung by Gary Barlow, who manages to sound like he’s mostly asleep and only doing it for the paycheque. Phil Lynott’s throaty, gargly Parson Nathaniel is now Maverick Sabre with some weird mishmash accent and the beautiful, emotive voice of Julie Covington has been replaced by that of Joss Stone, which is more operatic JCB than concerned but fatally optimistic angel.

The original score has been “updated” with some odd little riffs of electronica and bass, which serve no purpose other than to indicate that this is New! Improved! Hip! and On Trend!

“Hey kids! We know you like dubstep and psytrance these days, so we put in some tweaks just for you!”

Then there’s the script, which has also been altered. There’s an entire additional passage of exposition-heavy dialogue, in which the Journalist explains how the Martians gave up sex and got rid of bacteria. This is, obviously, based on the original work, but part of the joy of the original is that it stands on its own — there is no need to have read the book. When I heard this, I stopped what I was doing and stared at my player. “How in the hell did he find that out? He’s been trudging round a red-weed infested London trying to survive, not conducting scientific research into the mating habits and pathology of the alien invaders!”

I haven’t seen this in the theatre, where they have introduced whizzy special effects. I don’t especially want to now that I’ve heard it. The original didn’t need them, as it was carefully crafted to do without. The 2012 version has suffered from revision and, possibly, part of that is because there are whizzy special effects in the show.

Only one thing stood out as remarkable. Remember I was talking about Ulludubulla Vol. 2? That album starts with an interesting spoken word piece by Papa Ootzie, looking at the Eve of the War from the point of view of the Martians.

“The problem is, of course, the humans,” are the last words spoken in the epilogue, and they sounds suspiciously like a straight lift from the above track.

Unless you are the sort of person who buys things just to have them in the collection, I wouldn’t recommend this version. The original is by far superior in every way, from score to script to performance. Get a copy of that, instead.

Sam doesn’t like Sinbad

by ravenbait on Aug.26, 2012, under Reviews, television

![]() This week Frood and I finally gave up on Sinbad, the new fantasy series being broadcast on Sky 1. Halfway through episode 7 we realised we actually couldn’t give a stuff about any of them and so went in search of something else to watch.

This week Frood and I finally gave up on Sinbad, the new fantasy series being broadcast on Sky 1. Halfway through episode 7 we realised we actually couldn’t give a stuff about any of them and so went in search of something else to watch.

I had been looking forward to it despite the cringe-worthy CGI in the trailers. It was made by Impossible Pictures, who brought us Primeval — a series I enjoyed, for the first 2 seasons anyway. The premise seemed decent enough: young man in the prime of youthful folly is cursed by his Grandmother so that he has to spend the rest of his life at sea, hooks up with a bunch of people who are also on the run for one reason or another, adventures ensue.

Let’s face it. It’s basically Blake’s 7 meets Prince of Persia.

The programme starts off with Sinbad (Elliot Knight) —who wears as much eyeliner as a Sisters of Mercy fan for no reason that has been made clear— in a bare-knuckle fist-fight with another young man. It’s the sort of competition-fighting-for-money used as shorthand for “can handle himself and is a bit bad and dangerous” in numerous other works. In this instance, like so many others, the need for the star to have beautiful bone structure and saucy sex appeal means that he doesn’t get to suffer the usual thickening of facial features and scarring concomitant with the sport.

His opponent dies, in a manner suggestive of evil machinations and political intrigue. Said opponent then turns out to be the son of local bigwig Lord Akbari (Naveen Andrews), of course, who promptly goes completely ballistic and kills Sinbad’s brother in revenge. BECAUSE THAT’S WHAT ALWAYS HAPPENS. Sinbad escapes from jail and returns to his Grandmother, who, upon finding out what he has done, curses him so that he cannot spend more than a cycle of the sun on dry land hereinafter. AS YOU DO. Meanwhile Akbari is still frothing at the mouth and insisting that murdering Sinbad’s brother is insufficient payment for the loss of his son, because his son was a high status person and Sinbad’s brother was no better than the dirt under his feet. He employs the evil sorceress Taryn to find Sinbad for the purposes of torture and death. AGAIN, THE OBVIOUS RESPONSE.

It took me a while to work out how they managed to make something so ridiculously melodramatic so dull, and it comes down to the characters.

Take a wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey trip back to the 80s and consider the aforementioned Blake’s 7. Stripped to the fundamentals, the premise was pretty much the same. A ragtag bunch of people on the run find themselves a ship, form an unlikely crew and head off to have adventures while pursued by a powerful entity. The effects were terrible, the budget next to nothing, and it was absolutely brilliant. The characters had depth and vitality, and were played by the actors in a way that made them believable. The plots were there to serve the characters and give them a stage in which to express: never were the characters shoe-horned into some implausible behaviour because it made the plot work. Avon’s constant deadpan snark didn’t let up for a minute, whether he was having an argument with Orac, insulting Villa or flirting with Servalan. Villa was never forced to turn heroic (although he was occasionally the hero) in order to give him a more palatable character.

Servalan had depth, character, motivation and was both admirable and admired.

Sinbad, on the other hand, introduced us to Sirens, Death, tattooed ladies, a magic gambling den, CGI monsters and black magic chicken sacrifices, but by the end of episode 6 had failed to explain why Taryn was such evil bitch. There was nothing to explain why Sinbad’s grandmother would take the frankly bizarre step of forcing her only surviving grandson to risk dying a painful, horrible death every day — especially considering that he didn’t have access to a boat when she cursed him. Cook was still little more than a fat, bald bloke obsessed with spices who occasionally dispensed nuggets of wisdom in the manner of a fortune cookie. The nerd was still a nerd, and a hopelessly naive one at that.

The different way the story handled male and female characters made me faintly uncomfortable. All of them had something awful in their past which informed their current behaviour. The Viking, along with his Viking chums, apparently raped, pillaged and slaughtered in the manner of a badly-researched Berkserker. But he was a changed man, and prepared to give himself up to a gang of warriors for justice if they let him save his friend, so actually all that raping and slaughtering was completely forgiven.

Nala was once promised to Death by her people as a sacrifice, and that left her cold and stand-offish. She turned Death down, even though it might kill her new friends, and she was still cold and stand-offish and, really, didn’t change at all except that somehow that made it rain. Kind of. What?

Rina was a thief, who kept stealing stuff, even to the point of stealing everyone else’s valuables when they needed them most. But she was sold into slavery as a child by her parents, and used that memory to defeat a (female) demon, so everyone liked her after that. She hadn’t changed, it was just that she used her degradation in the service of saving the menfolk, so that made it worthwhile having her around.

And Taryn, arguably the most potent of the female characters. Evil for the sake of evil. Compare with Lord Akbari, whose insane, murderous intent could at least be hand-waved as the effect of extreme grief.

I don’t like Sinbad. There’s this weird, corner-of-the-eye disparity between the handling of the male characters and the female ones, and not in a good or justifiable way. Plus it’s another instance of the plot being the over-riding driver, resulting in characters doing implausible things because the plot requires that they do so.

I think it’s time to buy the Blake’s 7 box set to remind myself of how such a show should be done, before they ruin it with a remake.

Sam Reviews: Minister of Chance Episode 3, Paludin Fields

by ravenbait on Aug.17, 2012, under Reviews

![]() Long-time readers of this blog —as well as a good number of Californian wine makers, wine drinkers, restaurant staff, farmer’s market attendees and stallholders, and the passengers on May 7th’s flight VS020— will know that I am a big fan of Radio Static’s Minister of Chance. This crowd-funded, Doctor Who spin-off audiodrama has production values, acting quality and writing to match anything put out by Team Moffat, and I’d go as far as to say it exceeds in some respects because it doesn’t have visual effects to fall back on.

Long-time readers of this blog —as well as a good number of Californian wine makers, wine drinkers, restaurant staff, farmer’s market attendees and stallholders, and the passengers on May 7th’s flight VS020— will know that I am a big fan of Radio Static’s Minister of Chance. This crowd-funded, Doctor Who spin-off audiodrama has production values, acting quality and writing to match anything put out by Team Moffat, and I’d go as far as to say it exceeds in some respects because it doesn’t have visual effects to fall back on.

Episode 3, Paludin Fields, is the latest in this highly-anticipated production. It reunites some of the great and the good of British science-fiction acting talent (Paul Darrow, Sylvester McCoy, Paul McGann, Jenny Agutter) and introduces some equally talented new voices, including Tamsin Greig (Black Books, The Green Wing, the Archers) and Beth Goddard (X-Men: First Class, Ashes to Ashes).

The Minister of Chance, for those unfamiliar with the series, takes place in a world (I use the term loosely, for reasons that are obvious if you listen to it) of politics divided by a religion where the priests are witches and the currency is ineffective magic. To question the power of magic is to invite the kind of attention the Spanish Inquisition turned on heretics. Think Umberto Eco’s In the Name of the Rose, where the Inquisition is instead employed by an invading army to root out scientists, even though they make use of rockets and guns.

There are several interweaving plotlines, each driven by a main character conflict. The primary plot arc is that of the Minister himself, played with aplomb by Julian Wadham, and Kitty, believably voiced by Lauren Crace. The Minister is a Time Lord (although this has not been explicitly stated) and Kitty is a young girl who is not what she appears to be, as she has abilities not generally found in the populace. The pair of them are on a mission to stop the Horseman, who may or may not be another Time Lord, but is definitely a bad egg. Durian (Paul McGann) wants to start a war, although it is not yet clear whether he is doing so to take over as Witch Prime (Sylvester McCoy) or whether the war itself is what he wants, for an as-yet unrevealed purpose, and a coup is just a beneficial by-product. I was reminded of Prince Humperdink and his war on Guilder. Jenny Agutter’s Professor Cantha has a story arc to herself. In this episode her pacifist ideals are tested most sorely by the leader of the resistance (Beth Goddard) and, apparently, to breaking point. Although we have been there before and found her more than capable of fooling those who would have her turn to violence in their service.

I’ve already praised the sound effects in past reviews, so it will come as no surprise to learn that the soundscape in Paludin Fields is equally immersive and used to great effect to distinguish between the different settings and arcs. There are a number of jumps between the various plots, and it takes no more than a second or two to know which one is coming. The swamp life of the marsh is as distinct from the background murmur of the Coven’s assembly as it is from the echoing of an abandoned and ransacked library. Such is the attention to detail in the soundscape that I wouldn’t be at all surprised if two different listeners, when asked to describe what the various locations look like, came up with something similar enough to be recognised as the same place by someone who has never heard of the series. So I’ll concentrate on the story and the writing rather than the superb acting and production.

Episode 3 introduces further complexity to a story already full of depth and flavour. There is the Sage of the Waves (I wonder where they got that character name), played by Tamsin Greig, who would appear to be another refugee from the Minister’s world of technologically-advanced, scientifically über-literate, universal mystics; leading one to wonder what in the name of the Eye of Harmony happened to scatter them all over this steelpunk world of misogynistic pubs and frog-infested marshes. We are introduced to the Resistance, who rescue Professor Cantha, although this turns out not to be the blessing it first appears. We learn a bit more about Kitty’s unusual nature and, best of all, we learn more about the underlying principles governing how things work here.

I especially loved the Minister’s explanation to Kitty of why his talisman necklace was so important. It was a sublime piece of plausible hand-waving that I, as a fellow writer, can only admire: any writer who can explain something impossible in such a way as to make it sound not just possible but obvious is doing a fantastic job.

I also enjoyed Professor Cantha forcing the ex-librarian to recite the Theory of Fields she taught him in school as a counter to the resident magical explanation of “things just appear, by magic”. The populace has been beaten into believing it’s not just a rabbit in a hat that got there by magic, but every rabbit.

In the beginning was the data, and the data was complex and dynamic, and from the data came forth all the laws and forces of the world. And first amongst there was Causation, for for every effect there is a cause.

“If we look upstream do we not find a spring?”

Taken with the Minister’s explanation of how his talisman works, what it does and to whom he has given it, life is going to get very interesting on Tanto in Episode 4.

As I said, MoC is crowd-funded, and the campaign to fund Episode 4 is already well under way. There are some nifty rewards on offer for those who help, including the opportunity to have Paul Darrow record a voicemail message for your answering machine (now is probably not the time to confess to having the Blake’s 7 soundboard on my HTC — Orac alerts me to every text message). There are loads of creative projects out there asking for help with funding, and I’m well aware of the need, in the current financial climate, to pick and choose which ones to support. Episodes 1 – 3 are available free of charge, so you don’t have to take my word for it, but I’m certainly going to be putting money where my mouth is. I really hope you enjoy this as much as I have and will find even as much as the price of a pint of beer or a bottle of cheap Cabernet Sauvignon to help them on their way.

Sam Reviews: Prometheus

by ravenbait on Jun.09, 2012, under movies

![]() I should make something clear from the very start: Alien was my diving board into the world of science fiction in film. It wasn’t ET, or Star Wars, or Star Trek. For me these were not science. They weren’t real. They were fantasies, soap operas, adventure tales. They belonged with Black Beauty, Bonanza and Scooby Doo. Even back then, as a girl learning the OILRIG mnemonic for chemical reactions (Oxidation Is Loss, Reduction Is Gain), I felt that science fiction was something edgier and harder than I was finding on the television or the movie screen. It was something I was only finding in books, where the mechanics and the plausibility couldn’t be glossed over with a veneer of special effects and explosions.

I should make something clear from the very start: Alien was my diving board into the world of science fiction in film. It wasn’t ET, or Star Wars, or Star Trek. For me these were not science. They weren’t real. They were fantasies, soap operas, adventure tales. They belonged with Black Beauty, Bonanza and Scooby Doo. Even back then, as a girl learning the OILRIG mnemonic for chemical reactions (Oxidation Is Loss, Reduction Is Gain), I felt that science fiction was something edgier and harder than I was finding on the television or the movie screen. It was something I was only finding in books, where the mechanics and the plausibility couldn’t be glossed over with a veneer of special effects and explosions.

In space no one can hear you scream.

That was it. Right there. I was yet to experience the magnificent silence of Kubrick’s 2001. All I knew was that space is a vacuum, sound can’t travel in a vacuum because it is a compression wave, not a transverse wave, and Star Wars had given me far too many space lasers going “PEW PEW PIH-PEW-PEW-PEW!” followed by mega-explosions you could hear if you were standing on the moon.

No. Just no.

The gritty, industrial, supremely plausible sets of Alien, accompanied by the claustrophobic performances of the cast and, of course, the ultimate female action role model of Ripley (notable for not screaming), got me hooked on science fiction in film. As such, the film occupies a particularly well-kept pedestal in my mental gallery of things that have shaped my life.

You will understand, then, that I went to see Prometheus with something akin to a religious person going to witness some form of Holy Visitation, and I will save you the trouble of reading further, and exposing yourself to the ensuing spoilers, by telling you that the experience was rather like a Druid going on a trip to Stonehenge and discovering that it’s just a bunch of big rocks. Everyone around you is swooning over the mystic energies and the swirling chaos of Mother Earth reaching up and imparting visionary experiences of the Universe and Being At One With Existence and you’re thinking that it’s a shame it’s so close to the traffic and it’s not nearly as big as you thought it was going to be.

The film is extraordinarily pretty. It’s full of pretty. There is nothing in it that is not pretty. The scenery is pretty. The spaceship is pretty. The crew are all handsome or beautiful. Even old Weyland would have been good-looking, if they stripped off the cosmetics to reveal Guy Pearce (because, you know, there is a massive shortage of aging actors in the world who could have played that role — Ian Holm is still working and that would have been delicious). The Engineers are reasonably low on the ugly scale. Tall, built like rugby players, with a cupid’s bow lip (the male equivalent of the Jolie beestung pout). Charlize Theron is in fantastic shape, Fassbender’s grooming was lampshaded in the first section of the film — it’s all, you know, pretty.

Maybe that was part of the problem. I distrust pretty. Anything that pretty has to be distracting you from something and, when it comes to movies, it’s usually the story.

And, yes, there we go, the plot has so many holes in it you could use it to drain pasta. The characterisation of most of the characters bar the main four is so weak they might as well have been robots — there is little interaction, no badinage, nothing to distinguish them from NPCs at all. Plus, it makes the fatal mistake of a science fiction film: it gets the easy facts wrong.

Spoilers follow.

The trip to find their makers starts with archaeologists uncovering a cave painting on the Isle of Skye and dating it to a time so close to the last major glaciation that the idea of anyone being there to paint it stretches plausibility past the Young’s modulus. One should also note that the evidence is unclear as to whether modern humans (as opposed to genetically not-identical Neanderthals) were in the UK at all 35,000 years ago. That is just the first of the WTF moments that had me motorboating like 4hp Evinrude two-stroke on a bad oil/petrol mix. There was the instant carbon dating on an alien planet where the CO2 isotope ratio had not been characterised. There was the thing with the head and the electric re-animation — seriously, what was that all about? You cannot trick a head into thinking it’s alive by tickling the vagus nerve with a purple wand. Really, you can’t.

There were others. Oh yes, there were others. Like how the ship was equipped with an autodoc capable of performing any conceivable type of surgery, but which couldn’t deal with having a female patient. Because it was calibrated for a man. I know that was supposed to make the audience ask why it would be for a man when it was supposedly Vickers’s autodoc, but flagging the presence of someone on board we didn’t know about was better done by David’s conversation with Weyland over the neural link, rather than asking us to believe something so advanced couldn’t re-calibrate itself. It was one of the many foreshadowing points throughout the film, the most t-shirt worthy of which was Chekov’s Space Squid (I know it’s not strictly speaking a Chekov’s anything, as it was hardly an irrelevant detail, but Foreshadowing Space Squid is more of a band name than a t-shirt).

Scott’s film has won praise, and I’ve even seen people accuse those who don’t like it of being stupid, of failing to “get it”. Well, hands up. I failed to get it. Oh I got the whole “be careful what you wish for” fable, and I don’t have a problem with a religious scientist. I have a problem with a scientist who is not only an archaeologist but also a forensic xeno-pathologist, because the level of experience needed for that level of expertise in both is not realistically achievable in someone of Shaw’s age.

There’s an automatic defensive reaction from writers who have honed their craft to people suggesting writing is just something you can do; that anyone who can string a few words together deserves to be published. I understand. When you’ve worked at your craft that effort should be recognised. But I have a huge beef with writers inventing characters who are polymaths in specialisations. It cheapens the work and effort of scientists who have spent decades achieving that expertise. It’s almost as bad as when people think their opinion on a scientific topic is as valid as an expert’s because they’ve seen a Horizon documentary about it or read the wikipedia article. I could have understood David being the one to examine the head, just as Ash had been the one to conduct the examination in Alien, but why get Shaw to do it? Why was their medical officer less skilled than their archaeologist?

Why would a bunch of scientists head 4 years into space to an unknown planet without finding out why they were going and what part of their expertise would be required? Why was any one of the other individuals picked? We didn’t ever get to find out enough about them to know, or even to care about their eventual fate. Was their biologist picked for his stupidity? What sort of biologist was he anyway? What sort of geologist was Fifield? Or was he picked for his hair-trigger temper and his tattoos? When the biologist and the geologist said they were going back to the ship, how come they ended up wandering around in the tunnels? The entire crew seemed to have been chosen according to the criteria of a reality-TV show rather than a science expedition, which makes me wonder if the big secret was that Weyland had also sold rights to a television company.

This was a science-fiction film that didn’t pay attention to the science.

How did they happen across the place where the plot was scant minutes after entering the atmosphere? How did a ship that shape and size carry enough fuel to manage landing and take-off? How did the Space Squid get so big with nothing to eat? The original Alien got big by nomming upon the crew of the Nostromo. There’s a conservation of mass issue, there, unless the Space Squid ate the autodoc. How did Shaw manage to belay the robot down a cliff with nothing holding her lower abdomen together bar a few staples on the outside?

There were many other questions.

Prometheus was billed as a film that would make the audience question, and I did. What it didn’t do was make me ponder the big questions of who we are as a species and how we came to be here. It didn’t make me feel like re-reading Chariots of the Gods (although, to be fair, there’s not much that would because it’s drivel). I suspect that the questions we were supposed to focus on were those to do with our evolution. How come the Engineers’ DNA matched ours exactly when our DNA differs from a chimp’s by 1% and a gorilla’s by 2%? Did they seed all life on earth and we failed to evolve? Or was Scott implying that we somehow evolved from a squiggly strand of denatured alien DNA to match those aliens in every genetic detail (but not in looks, though, because we don’t live in Space Heaven and there’s that whole nature-nurture thing) and that was why they were coming to wipe us out? Were we too much like them? Did they see us as competition? Did they think that one species like them in the Universe was already too much? Was this a film about hubris? Arrogance?

I think it was. And, in a way, it was successful at that, because there is an arrogance in the implication we are supposed not to notice or care about the basic errors and implausibilities. I don’t mean things like the technology or the idea that we could travel so far in such a short time: I’m talking about the little things, the things that should not have been wrong, that could have been right with a little more thought or care.

To get back to where I started this, it was when I started comparing this film to Alien that I began to grok what bothered me so much about it. Shaw’s painfully extended battle with her unwanted pregnancy did not come across as plot but as fanservice. Ripley, arguably Hollywood’s most significant strong female character, died “giving birth” to an Alien Queen. Shaw cut the Space Squid out with a device meant for a man and killed the Engineer with it. Take that! Shaw’s sterility wasn’t really a vital part of her character motivation, because other than a brief, weepy argument with Holloway it didn’t have any effect on her behaviour. Rather it seemed to reflect Ripley’s forced state of childlessness caused by decades lost in hypersleep and the loss of Newt. David wasn’t a Data-like prototype but a fully-fledged, functioning robot who seemed far in advance of either Ash or Bishop; and who possessed a self-awareness that allowed him to distinguish himself from humans — and consider himself superior. Shades of Alien: Resurrection there. Prometheus riffed so hard on the franchise that the story, the characters and the setting came across like fan-fiction written by someone who thought the original stuff was so brilliant it didn’t matter if this new story was full of holes left by jamming his favourite elements together in a big pot and not cooking them properly.

I thought Theron and Fassbender were great, Rapace did what she could with a character that needed to be much better written, Marshall-Green was left treading water with a character that lacked any believable sense of conviction and Elba managed to put more character into 3 lines of dialogue than the other NPCs had between them. The opening sequence was breathtaking, and my fangirl hard-science squee was jumping up and down in excitement at the vapour curling over the lip of the giant flying saucer. I just wish the rest of the film had followed through on that promise.

You may feel differently, but I like a bit more science in my science fiction.

Sam reviews: Tricks of the Mind

by ravenbait on Nov.13, 2011, under books, Reviews

![]() I’ve just finished reading, by way of light evening entertainment, Derren Brown’s Tricks of the Mind. Before I review it, I’d better ‘fess up about my ambivalent feelings towards Mr Brown.

I’ve just finished reading, by way of light evening entertainment, Derren Brown’s Tricks of the Mind. Before I review it, I’d better ‘fess up about my ambivalent feelings towards Mr Brown.

I am not fond of hypnosis used for the purposes of entertainment. This is an understatement so vast you could use it as an air-craft carrier and rescue the entire fleet of Harrier jump jets without them ever having to make a VTOL again. It takes an effort of persuasion or morbid curiosity regarding a particular stunt for me to watch any such performance on the television. The only Derren Brown show I have ever enjoyed was the one in which he went around debunking charlatans who were profiting from the gullibility of others (the school teaching blind people to see energy, in an effort to give them the kind of preternatural sight afforded by melange overdose to Paul Atreides, was an excellent case in point). I found his Zombie show repellent, believing, as I do, very strongly in the notion of informed consent.

My problem with Mr Brown comes down to that one critical idea: informed consent. As his show is one of magic and illusion, by its very nature he cannot explain how he does it. He is not the masked magician giving away Magic’s Greatest Secrets (not that I’m convinced by that, either). It is necessary for him to refrain from explaining himself and I appreciate that. It means, however, that the people he involves in his illusions and “experiments” cannot know precisely what he is going to do to them. It wouldn’t be so entertaining for the audience, otherwise. He needs them to be, as he describes the subject of Zombie in his book, of “naïve status”. Notwithstanding his insistence that

“It is very important to me that they enjoy themselves immensely and finish with a very positive experience of the process.”

I take issue with putting someone through any form of experience that, let’s be blunt, messes with his head, without prior full disclosure.

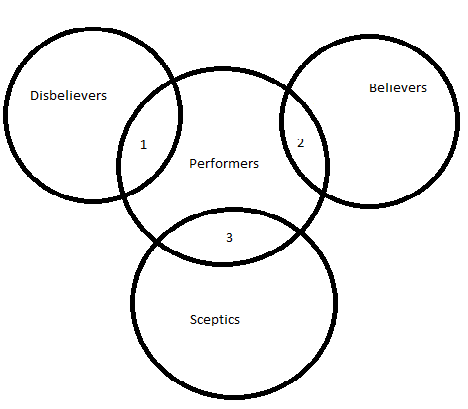

Mr Brown and I do share common ground, however. In a Venn Diagram of believers (e.g. Dion Fortune, say, or Kevin Carlyon), disbelievers (Richard Dawkins) and sceptics (Charles Fort), there is a cozy overlap of a set that includes everyone from Paul Daniels to Derek Acorah and Rupert Sheldrake.

There is an unfortunately large subset of performers that is contiguous with the middle set — the confidence tricksters, who know damn well they themselves are not psychic (whatever they feel about the supernatural in general) but who pretend to be psychic in order to extract money from gullible people. There is a special level of Hell reserved for people like them, and I expect the demon in charge is by now fed up with all the correspondence from me suggesting suitable punishments.

Snotgobbet, demonic secretary: You have email, my Lord.

Beelzebub, Master of Hell: FFS. It’s that mad Scottish woman again. How many is that this week?

Snotgobbet: That’s the third, my Monstrousness.

Beelzebub: She must be busy. Or slacking. We usually get more than that. Hmm. Do we even own that much chilli oil?

Snotgobbet: I will ask the Quartermistress, oh Ruler of Negative Empathy. If not, I am sure she can procure some from a suitable wholesaler.

Beelzebub: Oh, very well then. I’ll sign the order. Let me know when it comes in and fetch me the Dremmel.

Mr Brown and I share that particular distaste, at least.

The book promises to take you on “a journey into the structure and psychology of magic”. But we all know that what is written on the back of the book may not necessarily reflect what the author thinks the book is about. Mr Brown does this in the preface, explaining, by way of what is presented as an amuse bouche of an anecdote, that it teaches more about the various skills he employs to “entertain and sexually arouse the viewing few”.

The book promises to take you on “a journey into the structure and psychology of magic”. But we all know that what is written on the back of the book may not necessarily reflect what the author thinks the book is about. Mr Brown does this in the preface, explaining, by way of what is presented as an amuse bouche of an anecdote, that it teaches more about the various skills he employs to “entertain and sexually arouse the viewing few”.

On this front I have no disagreement. Mr Brown does indeed discuss the techniques he employs in his performances. He discusses mnemonics and hypnotism, sleight-of-hand and illusion, the power of persuasion, cold-reading, statistics, the way people are swayed by emotion, and the commonalities of the human experience that can be relied upon to make an individual treat a generic, stock answer as being a treatise on the dark corners of her soul. What it does not do is tell you exactly how he performs any one of his particular tricks. Indeed, he specifically says that he deliberately obfuscates so that what might look like a memory trick is actually manipulation and misdirection and vice versa.

Do not buy this book expecting to find out precisely how he pulled off Russian Roulette, or how he made a table levitate for Dr Robert Smith of UCL (although there is a good picture of the latter in the glossy middle pages). Do buy this book —or borrow it from a library— if you would like to read about Brown’s fascination with mnemonics and what he got up to as a student. Get it for the discussions of how what seems self-evident doesn’t hold up when analysed mathematically (always change your mind when presented with the last two boxes in the Monty Hall problem). If you liked the depiction of Hannibal Lecter’s Memory Palace you may well enjoy the exercises that start you on the road to creating your own.

He has a bee in his bonnet about pseudo-science, which is fair enough. He is only slightly less harsh about homeopaths and alternative medicine practitioners than Ben Goldacre, although makes no mention of TAPL. He does, however, lump a big section of the environmental lobby (including, by textual proximity, Greenpeace) in with the anti-MMR brigade, and misrepresents the Precautionary Principle used in environmental protection to a degree that makes it seem like environmentalists are as risk-averse as the mythical PC Health & Safety brigade (the one that insists that a banana must be straight just in case someone wishes to use it for a purpose other than consumption and runs the risk of injury as a result of excessive curvature).

He discusses, for instance, the banning of DDT and Carson’s Silent Spring, stating that he read in a book by Dick Taverne that “no tests have ever been replicated to show that DDT damages the health of human beings”, thereby missing the point, a bit, about Carson’s work. DDT’s effect (or lack thereof) on humans is only a small part of the picture. It was banned because of its effect on wildlife. Equally, GMO crops and the questions about growing them don’t have as much to do with their effect on the people eventually eating them as on the ecosystem as a whole. In trying to slam the green lobby for preferring “ideology over evidence” he shows a very human-centric view, and makes himself seem something of an idealogue —just a different sort of idealogue. One that sees the odd scientific fact and juicy rational tidbit and pounces on it, much as he describes those who believe in spiritualism and horoscopes as doing. I suppose that this only goes to show that we all do it, whether we like it or not, and a little amount of knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

I wouldn’t presume to offer an educated view on magic, memory and illusion. I appreciate Mr Brown’s desire to debunk charlatans and pseudo-scientists, but I do think he should be a bit more circumspect in how he chooses his examples.

That aside, the book is far more entertaining than his television shows. I still will not be persuaded that the more extreme examples of what he does are not a form of assault that is television-friendly.

At the end of the day, the book is also a performance. I doubt, despite his assurances, that the reader will learn much of the real Derren Brown. He swings from being deliberately self-deprecating to being self-aggrandising in a way that we are no doubt supposed to take tongue in cheek. On the other hand, as he says, who you are in an objective sense isn’t so much who you believe you are as how you present yourself. It’s not about what you think, feel or intend but about what you do. If what Derren Brown does is hypnotise people without asking into believing they are fighting zombies, or take potshots at the environmental movement because people who worry about the effect of bioaccumulative pesticides on apex predators are “eco-fundamentalists”, then I am content to carry on avoiding his shows and let him make his money from people who enjoy that sort of thing.

But I might be persuaded to read another of his books.

Sam reviews: The Last Werewolf

by ravenbait on Nov.05, 2011, under books

![]() It was with a mix of sympathy and amusement that I read this article on iO9 responding to Glen Duncan’s piece on Colson Whitehead’s Zone One in the New York Times magazine. On the one hand we have the opening paragraph, which is clearly a rather unwarranted set of clichés and prejudicial presumptions:

It was with a mix of sympathy and amusement that I read this article on iO9 responding to Glen Duncan’s piece on Colson Whitehead’s Zone One in the New York Times magazine. On the one hand we have the opening paragraph, which is clearly a rather unwarranted set of clichés and prejudicial presumptions:

A literary novelist writing a genre novel is like an intellectual dating a porn star. It invites forgivable prurience: What is that relationship like? Granted the intellectual’s hit hanky-panky pay dirt, but what’s in it for the porn star? Conversation? Ideas? Deconstruction?

On the other we have the undeniable fact that Duncan clearly likes the work in question:

There will be grumbling from self-¬appointed aficionados of the undead (Sir, I think the author will find that zombies actually…) and we’ll have to listen for another season or two to critics batting around the notion that genre-slumming is a recent trend, but none of that will hurt “Zone One,†which is a cool, thoughtful and, for all its ludic violence, strangely tender novel, a celebration of modernity and a pre-emptive wake for its demise. If this is the intellectual and the porn star, they look pretty good together. For my money, they have a long and happy life ahead of them.

As it happens, Duncan’s The Last Werewolf has just moved off the top of my currently reading pile, and while I do have issues with Duncan’s blunt stereotyping of both intellectuals and porn stars, I think the only work he’s hurting is his own.

There is little chance of anyone trying to argue that The Last Werewolf is not a piece of genre fiction — and, before anyone starts screaming blue bloody murder, I do not think that this is a bad thing. Personally I get fed up with the insistence on labelling and hierarchies just as I get fed up with people who complain that action movies are somehow inferior simply because they tick all the boxes in the correct order. A book isn’t necessarily bad if it has as its primary goal the attempt to entertain. Not every single piece of written word has to have as its underlying purpose the statement of something profound about the human condition.

Nor is this to say that genre fiction can’t have something profound to say about the human condition. Genre fiction has a great deal to say about the human condition, and can be as thought-provoking as any so-called literary work.

Indeed, The Last Werewolf reads not so much as a depiction of lycanthropic existence as an attempt to pen a study of graceless ennui caused by over-stimulation, perhaps as an allegory for the internet generation’s desensitised state of been there, done that, got the two-girls-one-cup-happy-slap-t-shirt.

It did not light any fires chez Raven. It was a decent book — I have no showstopper complaints about it. I read it right through to the end and didn’t have to stop to rant (much) at any point. The prose was well-constructed, the imagery suitably lyrical, and the writing style avoided being clunky at any point. Marlowe’s character had a very definite voice, which meant the first-person perspective worked well. The idea that werewolves in this world were not eating the flesh of their victims so much as their histories and memories was a great one: taking a life meant taking a life, leaving one to infer that a werewolf’s lifespan was limited by sheer capacity more than biology. I enjoyed the throwaway trivia, for example that the expected pack structure was not there because female werewolves were in such short supply any other male would be regarded as a sexual rival. While I don’t want to give any plot spoilers, I appreciated that the female characters were, in their own way, powerful, and in some cases more powerful than gender stereotyping might lead one to expect.

Yet there were too many clichés spoiling the originality. Surely we have had enough of the vampire hates werewolf, werewolf hates vampire trope? Duncan went to some lengths to explain it but I sighed when Pratchett did it and Duncan does not have a pre-loaded soft spot in my heart as Sir Terry does.

I had issues with the pacing. The first two thirds of the book read like one of those movies in which there is lots going on but, inexplicably, nothing actually seems to be happening. This was no doubt meant to reflect Marlowe’s loss of enthusiasm for life, however it left me feeling oddly unmoved by any of the dramatic scenes, which meant that they were rendered not all that dramatic. Not enough was made of Marlowe’s access to the memories of those he had consumed and there were moments when I was left thinking “show, don’t tell”. At one point, in the last third of the book, there was an example of this so egregious I found myself thinking “FFS, couldn’t you at least try?”

Once again we had the assumption that living a long time means being able to accumulate vast riches. I suppose we wouldn’t have had all the globe-trotting if he’d been a pauper rather than someone for whom a cool twenty million is mere pocket change and I suppose one could argue that 200 odd years is enough time to get rich. Marlowe started off rich, though, which was irritating. I feel that there should be only so much disconnect between the reader and the protagonist, and there are big enough hurdles in getting to grips with the idea of being obliged to consume a person and his entire living memory once a month, as well as the idea of being so full of other lives and bored with one’s own life (not unhappy with it, but bored) that a violent death seems the preferable option without having to imagine being financially carefree in a way that only a tiny fraction of a percent of the world’s population experience.

You see, there was something that came close to being a deal breaker: Marlowe as a werewolf was the hybrid, bipedal, intelligent man-wolf type, nine feet tall and apparently unconstrained by conservation of mass.

I read advice somewhere to the effect that the reader will suspend disbelief for one thing and one thing only, so the writer would do well to make sure that one thing is the most implausible part of his story and that his plot hinges on it. Unfortunately for my enjoyment of this book the most implausible part of the story was that an ordinary-sized man can turn into a bipedal wolf-creature that is nine feet tall and stronger than Marius Pudzianowski. I let that slide, but then found myself unable to stop grousing about other major implausibilities.

Duncan’s review of Zone One left me wondering whether he thought it was the porn star or the intellectual who was aiming below his or her station in life. It is easy to infer he was describing a form of superiority when he wrote:

“…he’s a literary writer, hard-wired or self-schooled to avoid the clichéd, the formulaic, the rote.

Given that Duncan’s own work is a literary kind of genre fiction, taking this analogy at face value leads inevitably to one question: Does Duncan see himself as the porn star or the intellectual?

Because, quite frankly, in The Last Werewolf he has produced something that, while being entertaining and by no means the worst werewolf book I’ve ever read, fails either to deliver on the porn-star’s delight in his material or the intellectual’s hard-wired avoidance of rote and cliché.

If you want a good book about werewolves that examines the human condition, I recommend Kit Whitfield’s Bareback.